The pregabalin Supreme Court decision – what actually is the plausibility standard now?

0November 21, 2018 by IPAlchemist

I went last night to the IBIL event that discussed last week’s pregabalin decision. There was a stellar lineup in the panel, and an equally august audience in attendance. But there was a major flaw. The panel jumped straight to discussing how the Supreme Court decision compares with the situation in other countries, and whether it was correct, without first establishing what the decision actually says. What now is the standard for plausibility? Has it changed, and if so how?

I am pleased to be in good company in finding it difficult to discern a difference in legal standard for plausibility as set out between the majority decision (Lord Sumption) and the minority dissents (Lord Mance and Lord Hodge) – Lord Hoffmann last night said that he could see little difference in their respective positions. So what is going on?

Lord Hodge clearly states that he disagrees with Lord Sumption, stating at [180]:

Where I differ from Lord Sumption is that, in agreement with Lord Mance, who has analysed the three cases of ALLERGAN, IPSEN and BRISTOL MYERS SQUIBB, I do not interpret those principles as requiring the patentee to demonstrate within its patent a prima facie case of therapeutic efficacy.

Lord Mance similarly disagrees, stating at [193]:

In my view, Lord Sumption’s analysis imposes too high a threshold, and imposes a burden on a patentee which the case law of the Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office does not justify. I prefer the approach advocated by Mr Mitcheson, but rejected by Lord Sumption in para 30 of his judgment.

What is rejected by Lord Sumption in para 30 of his judgment is the argument that

it is necessary for the patentee to disclose reasons for regarding the claimed therapeutic effect as plausible only when the skilled person reading the patent would be sceptical about it in the absence of such disclosure.

Later on at [33] Lord Sumption states

It must always be necessary for the patentee to demonstrate that he has included in the specification something that makes the claim to therapeutic efficacy plausible.

And at [35] he summarises:

The fundamental principle which [these judgments from the EPO Boards of Appeal] illustrate is that the patentee cannot claim a monopoly of a new use for an existing compound unless he not only makes but discloses a contribution to the art. None of them casts doubt on the proposition that the disclosure in the patent must demonstrate in the light of the common general knowledge at the priority date that the claimed therapeutic effect is plausible. On the contrary, they affirm it.

Lord Sumption also disagrees with the Court of Appeal – at [36] he explains:

They [the Court of Appeal judges] considered that the threshold was not only low, but that the test could be satisfied by a “prediction … based on the slimmest of evidence” or one based on material which was “manifestly incomplete”. Consistently with that approach, they considered (paras 40, 130) that the Board’s observations in SALK laid down no general principle. I respectfully disagree. The principle is that the specification must disclose some reason for supposing that the implied assertion of efficacy in the claim is true. Plausibility is not a distinct condition of validity with a life of its own, but a standard against which that must be demonstrated. Its adoption is a mitigation of the principle in favour of patentability. It reflects the practical difficulty of demonstrating therapeutic efficacy to any higher standard at the stage when the patent application must in practice be made. The test is relatively undemanding. But it cannot be deprived of all meaning or reduced, as Floyd LJ’s statement does, to little more than a test of good faith. Indeed, if the threshold were as low as he suggests, it would be unlikely to serve even the limited purpose that he assigns to it of barring speculative or armchair claims.

So what Lord Sumption appears to be expounding, which goes further than the plausibility test as previously understood (at least by me), is that it is not sufficient that it be objectively plausible that the invention works, based on the information in the patent and what was otherwise known at the priority date, but that the patent specification must actively disclose why it is plausible. Thus there appears to be a new disclosure requirement – “the specification must disclose some reason for supposing that the implied assertion of efficacy in the claim is true” (as quoted above from para 36).

There is considerable advocacy in Lord Sumption’s judgment, and reading it alone it is entirely convincing. It is only when trying to work out precisely how it differs from the views of Lord Hodge, Lord Mance, and indeed the Court of Appeal, that it becomes evident that the standard it purports to lay down, and how this standard has evolved from earlier English jurisprudence, is not clearly expressed.

But there is a bigger problem. Having set out a standard, albeit unclearly, Lord Sumption does not then apply it. When reversing the finding of Mr Justice Arnold that the specification satisfied the plausibility requirement for peripheral neuropathic pain, Lord Sumption did so not on the basis of a different applicable legal standard, and “not because there was anything wrong with the judge’s findings, but because those findings do not support his conclusion that the specification makes it plausible to predict that pregabalin will be efficacious for treating neuropathic pain.” [48]

He goes on at [50]:

The judge’s analysis of the implications for peripheral neuropathic pain of the data presented in the specification was based entirely on the common general knowledge that central sensitisation was “involved” in both inflammatory and peripheral neuropathic pain. The judge concluded from this that it was “possible” that a drug which the specification showed to be effective for the first would also be effective for the second, “although this would not necessarily be the case.” In my opinion this is a logical non-sequitur.

Thus, Lord Sumption seems to be saying that Arnold J’s analysis is not logically sound even on its own terms, and so he is reversing on that basis. Not on the basis that the threshold applied by Arnold J was too low, or that the patent failed to satisfy the new disclosure requirement articulated earlier.

I rather hope that I am wrong, but it seems to me that Lord Sumption has not actually applied in the operative part of his ruling the standard that he appears to have set out earlier. If that is the case, is the earlier standard even ratio decidendi? It is hard to see how this ruling from the Supreme Court can be applied to future cases.

A final comment on infringement. We have three dissenting views of what infringes a second medical use claim. They are all obiter. What we are supposed to do with them seems more a matter of philosophy than the practice of law.

Category Chemistry, Patents | Tags: IBIL, plausibility, pregabalin, Supreme Court

Teva v Gilead – C-121/17 provides some clarity on combination products

0July 26, 2018 by IPAlchemist

The CJEU gave its ruling yesterday in case C-121/17 in the case of Teva v Gilead. This concerns the SPC for the combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine (marketed by Gilead as Truvada ®), which was granted in the UK and which Teva and others were seeking to revoke. There was no SPC for the tenofovir alone, as far as I can tell, because the EU marketing authorisation for the mono product was granted within 5 years of the application date of the basic patent EP 0915894. Gilead has successfully argued that the patent, which did not mention emtricitabine, could serve as the basic patent for a combination SPC following authorisation of the combination, because claim 27 referred to:

A pharmaceutical composition comprising a compound according to any one of claims 1-25 together with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier and optionally other therapeutic ingredients.

In proceedings in the Patents Court, Mr Justice Arnold considered that the CJEU jurisprudence on combination SPCs was still insufficiently clear, so he referred yet another question on Article 3(a) of the SPC Regulation to the CJEU:

‘What are the criteria for deciding whether “the product is protected by a basic patent in force” in Article 3(a) of Regulation No 469/2009?’

He offered a view – that it related to the inventive advice or technical contribution of the patent – stating at [97]:

In my view, the answer is that the product must infringe because it contains an active ingredient, or a combination of active ingredients, which embodies the inventive advance (or technical contribution) of the basic patent. Where the product is a combination of active ingredients, the combination, as distinct from one of them, must embody the inventive advance of the basic patent.

The Advocate General disagreed and proposed that the criterion should be whether:

“on the priority date of the patent, it would have been obvious to a person skilled in the art that the active ingredient in question was specifically and precisely identifiable in the wording of the claims of the basic patent. In the case of a combination of active ingredients, each active ingredient in that combination must be specifically, precisely and individually identifiable in the wording of the claims of the basic patent.”

The CJEU has not gone with either of these proposals, but has instead set out a test which is a more nuanced version of the AG’s test and which I think, for the first time, is tolerably clear and can reasonably be applied to future cases.

The ruling states:

Article 3(a) of Regulation No 469/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 May 2009, concerning the supplementary protection certificate for medicinal products, must be interpreted as meaning that a product composed of several active ingredients with a combined effect is ‘protected by a basic patent in force’ within the meaning of that provision where, even if the combination of active ingredients of which that product is composed is not expressly mentioned in the claims of the basic patent, those claims relate necessarily and specifically to that combination. For that purpose, from the point of view of a person skilled in the art and on the basis of the prior art at the filing date or priority date of the basic patent:

– the combination of those active ingredients must necessarily, in the light of the description and drawings of that patent, fall under the invention covered by that patent, and

– each of those active ingredients must be specifically identifiable, in the light of all the information disclosed by that patent.

While emphasising that this is a matter for the referring Court, the CJEU makes clear how the test should be applied to the facts of the underlying case:

In the present case it is apparent, first, from the information in the order for reference that the description of the basic patent at issue contains no information as to the possibility that the invention covered by that patent could relate specifically to a combined effect of TD and emtricitabine for the purposes of the treatment of HIV. Consequently, it does not seem possible that a person skilled in the art, on the basis of the prior art at the filing date or priority date of that patent, would be able to understand how emtricitabine, in combination with TD, necessarily falls under the invention covered by that patent.

Like theologians poring over the latest papal encyclical, SPC enthusiasts have leapt on this judgment to try and work out what it really means. Unlike the gnomic utterances in Medeva (“specified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent”) and Lilly v HGS (“the claims relate, implicitly but necessarily and specifically, to the active ingredient in question”), some clarity and method is beginning to emerge.

What the CJEU is saying is that the active ingredient, or in the case of a combination product, each active ingredient in the combination, must specifically be indicated in the patent as being part of the invention. And by the “invention”, is not meant any consideration of the “clever bit” or inventive advance (as suggested by Arnold J) – the CJEU is relying only on the law that relates to the extent of protection and extent of invention – Article 69 EPC and Section 125 of the Patents Act. According to s125, the invention is “that specified in a claim of the specification of the application or patent, as the case may be, as interpreted by the description and any drawings contained in that specification”, and it is precisely that which the CJEU is referring to. The CJEU correctly rejected the AG’s opinion that focused on the claims alone, because Art 69 and s125 include the description and drawings as being part of the interpretative means. But the CJEU also said that the prior art can be taken into consideration, and it seems this would be relevant if the particular active ingredient in question was referred to in the patent indirectly in a manner that would lead the skilled person, in the light of the prior art, to the specific active ingredient.

By “specifically”, the CJEU means that the particular active ingredient must be somewhere indicated, and not simply a generic description that did not lead to the specific compound. The indication might be in the claims, in the description, or possibly in the prior art if, for example, the compound was sufficiently well known. How specific is needed is still a little unclear – obviously “other therapeutic ingredient” as in the current case is not enough (at least if the compound was not already known, but probably in any case). I would expect that a broad functional term would also not be enough. A therapeutic class might suffice, but I would expect that this might depend on how broad the class was, and how well known the particular active ingredient was within it. Hopefully two further CJEU cases will clarify this – in both the question is whether the term in the claim is specific enough to support an SPC. In the case of Sandoz v Searle, the claim specifies a broad structural formula, but not the exact combination of substituents leading to the specific compound, which is not disclosed in individualised form in the patent. In the Sitagliptin case, the term in the claims is a functional term. Good judgments in those cases would serve to clarify the situation a great deal.

So will patent attorneys now start adding lists of known drugs into patent applications for new chemical entities? And would this be effective to support a combination SPC? We may well see this happen, but I expect that if a whole pharmacopoeia of compounds is mentioned in the specification, the CJEU may ultimately rule that none of them is specifically disclosed as being part of the invention.

For the avoidance of doubt, I disagree with all of the jurisprudence on this topic. My preference would be a simple infringement test – if the active ingredient, combination or otherwise, would infringe the patent, then it should satisfy Art 3(a). But that ship has long sailed, and even the Swiss courts have now moved away from the infringement test. It seems that the best we can hope for now is clarity on the test that the CJEU intend to be used.

Category Chemistry, IP (Intellectual Property) | Tags: CJEU, Combination Product, SPC

IP Out Event – January Drinks

1January 31, 2018 by IPAlchemist

I really did not think I would be writing an event report of an event that had no speakers, but actually quite a lot happened at the IP Out drinks last night, and so I wanted to record a few thoughts.

It’s been less than 18 months since our first event, and we are already on our fifth. Feedback from attendees from questionnaires at our previous events continued to show support for the idea of a “social only” event, without any speakers or particular topic. So this time, for the first time, we held an event in a bar, rather than in the offices of a law firm, where all our previous events have taken place. We went for the New Bloomsbury Set, who gave us our own area and treated us very well. Since the organisation required for social drinks is much lower than for a speaker event, I am wondering whether we could make this a regular event on a fixed timetable. If we had it say every month, for example, would people want to come at that frequency?

Numbers were lower than at the more formal meetings, but we still had a decent turnout, and my impression is that a drinks event is not overall less popular, but rather that fewer people who identify as allies come if there is not a specific topic under discussion. That’s not a problem at all, but I do want to reiterate that allies are welcome at all IP Out events. I did worry that people would be deterred from attending an event where they had to buy drinks for themselves and each other rather than refreshments being kindly supplied by our host firm (and our host firms have always been very generous), but from what I saw that did not cause a problem at all.

Gratifyingly, from my rough count, about a quarter of people attending were at an IP Out event for the first time, so we are still succeeding in reaching out to new people, while remaining well-supported by our excellent committee and regular participants. I was also delighted to see that we continue to attract a wide cross-section of people from across the intellectual property law and related professions, which, as I discovered at the IP Inclusive AGM, is an aspect in which the IP Out group is really excelling. But it seems that we cannot say too often, so I am saying it again – IP Out is not only for patent attorneys, trade mark attorneys, solicitors, barristers, notaries, legal executives, members of the judiciary, trainees for those roles, and members of the judiciary, but is for anyone working in IP, regardless of your role, which, in a non-exclusive list, could include secretarial, formalities, records, paralegal, searcher, journalist, translator, patent illustrator, conference organiser, HR, IT, accounts, marketing, or office services. If you are in a patent and trade mark attorney firm, an IP law firm, the IP department of an IP law firm, an in-house IP department, legal publisher, search firm, translation firm, patent illustration firm, barristers’ chambers, or similar or related organisation that I can’t think of at the moment, we would love to have you join us for any event that you wanted to attend. They are all listed on our webpage here.

Thank you again to everyone who attended last night and contributing to such a splendid evening.

Category IP Out | Tags: IP Out drinks

Legislation published for UK to join The Hague Agreement – and why did we not know who the IP Minister is?

1January 24, 2018 by IPAlchemist

I wrote yesterday that I tend to blog when I have a thought that I want to get out of my mind. Well, today I have two thoughts.

First, The Designs (International Registration of Industrial Designs) Order 2018 (S.I 2018 No. 23) has just been published (thanks to Peter Groves @IPso_Jure for tweeting this). This is the final legislation that is required for the UK to join the Geneva Act of the Hague Agreement, which is an international system for the registration of designs (similar to the Madrid system for trade marks). The UK was already effectively a member by virtue of the EU’s membership, and so UK entities could already file applications under the Hague system – it is a “closed system” so only entities based in member jurisdictions can use it. However, membership via the EU only allowed a Community Design to be designated, not a UK national design. Shortly, it will be possible to designate a UK national design as well as, or instead of, a Community Design.

The legal power for this legislation to be passed, and for the UK to sign up individually to the international design registration system, derives from section 8(1) of the Intellectual Property Act 2014 , and it is a bit of a shame that the Government has taken so long to enact the necessary Statutory Instrument. Given the uncertainty about the scope of Community Designs in the event of Brexit, the ability to designate a UK national right in addition to an EU right will be welcomed by many users of the system.

The UK now needs to deposit its instrument of ratification, which I suppose will happen quite quickly, and then (under Article 28(3) of the Geneva Act of the Hague Agreement) three months later the UK will become a member of the system.

My second thought is that the legislation is dated 11 January 2018 and signed by Sam Gyimah. Now, I have been moaning (mostly on Twitter) since the government reshuffle on 8/9 January about the lack of clarity over who would be the next Minister for Intellectual Property (a position previously taken by Jo Johnson). Until today, the .gov.uk website described Sam Gyimah as “Minister for Higher Education” (only) and stated “Ministerial responsibilities will be confirmed in due course” – see the screenshots below. Today, this has changed to “Minister of State for Universities, Science, Research and Innovation” and intellectual property has been specifically listed as one of the responsibilities. (Thanks to @ipfederation for bringing this to my attention)

It is bad enough that it should take two weeks to set out where the ministerial responsibility for intellectual property lies. But the fact that this legislation was signed by Sam Gyimah on 11 January shows that he has in fact occupied this position the whole time. It also seems that those who attended the Alliance for IP reception on 17 January were told of the appointment. Why on earth should it take a further week to announce it properly?

Category IP (Intellectual Property), Political | Tags: Hague Agreement, Registered designs

The LGBT+ STEMinar 2018 – the conference for the future

1January 23, 2018 by IPAlchemist

I have been wanting to write a post about the LGBT+ STEMinar, but I was not really sure what I wanted to say. Having a thought in my head that I want to get out is frequently my driver for blogging, and when I don’t have it, things tend to get a bit delayed. In the meantime, others have written their accounts – you can see this on the website of the Royal Society of Chemistry (one of the several learned societies who sponsored the event) and this from my hero David Smith, a chemistry professor at the University of York.

It was one of the most tweeted conferences that I have come across, and the hashtag #LGBTSTEMinar18 will take you to a multitude of tweets and pictures. We were a trending hashtag on the day, and even attracted the attentions of a number of trolls, which most of us took as an affirmation of the significance of the event.

I have just come back from the annual general meeting of IP Inclusive, and this has finally spurred me to express a few thoughts about why the LGBT+ STEMinar is such an important event for me, and, from what I can tell from talking to other attendees, for many other people as well.

Firstly, although “interdisciplinary” is much talked about nowadays, it is extremely rare to attend an event that truly covers a whole range of disciplines within science. The programme is at the link here, and you can see that just in the talks there is chemistry, microscopy, astrophysics, biology, atmospheric physics and more. The posters were yet more diverse still. It is so rare to see scientists actively engaged outside their own discipline, and just sharing their enthusiasm for what interests them.

Secondly, the atmosphere at the conference was truly wonderful – people were respectful and engaged. The applause at the end of each talk had a quality not just of “thank you for finishing” but “really, thank you for sharing that with us”. There were no questions designed to show off the superior knowledge of the questioner, and people were respectful of their time allocations. And the socialising the evenings before and after the conference itself were great opportunities to chat to a whole range of fascinating scientists.

Thirdly, both the keynote speakers Beth Montague-Hellen at the beginning and Tom Welton at the end reminded me of just how far rights for LGBT+ people in the UK have come on in rather a short period of time of just a few decades. Being at the upper end of the age range of people attending, I am particularly conscious of this – not only was consensual sex between men decriminalised only the year before I was born, but also, when I came out at the age of 19, sex between men was still illegal for men of my age. This reminder is on the one hand very heartening, but on the other very concerning – what has been given in a short time can be taken away in a short time as well, and we cannot afford to be complacent. Many of these advances have taken place in only a few countries, and in much of the world LGBT+ people do not enjoy the freedoms that we do in the UK. And in the UK, even with the great progress that has been made, there is still much work to be done to promote LGBT+ visibility and inclusion both within the workplace and in wider society. It saddened me how many people present, a generation younger than me, spoke of less than full acceptance from their families and peers.

So it was also handy that we had a number of workshops on public engagement (that because of time pressures had to be run in parallel), exploring what we can all do to counter prejudice, and to increase visibility.

This year, my second to attend the conference, I was delighted to have my talk proposal accepted. I was very nervous, because I was aware of how few slots there were for speakers and how many excellent proposals had not been accepted. I spoke about the patent litigation on pregabalin, and the effect on the drug reimbursement price – truly interdisciplinary even by the standards of this most diverse event. I hope that I succeeded in my aim of communicating the fascination I have with how complex litigation unfolds and affects those involved, not just the parties to the litigation.

I also took along a poster about IP Out, and several people came over to talk to me about patents and about the work that IP Out is doing.

On a more personal note, it was lovely to have the event in York – every time I go there I am struck afresh by quite what a beautiful place it is. But I grew up in Yorkshire, and I cannot say that my memories are entirely happy, as it was not a forgiving environment for a boy who didn’t entirely fit in. So it is always with mixed emotions that I journey from London up the East Coast line. The transportation was also not kind to us, as there were train delays both the day before and on the day of the conference. Happily, though, I still made it.

In my title I called this the “conference for the future”, as I think that the event gave the participants the space to be authentically ourselves. We would like our environments, and especially our workplaces, to be like this all the time. In the meantime, for just one day a year, we have this. So I look forward to seeing everyone next year, which will be hosted by the Royal Astronomical Society and the Institute of Physics in London.

Category Chemistry, IP (Intellectual Property), Patents, Science | Tags: LGBTSTEMinar18

Why were the SPCs for Pregabalin allowed to lapse? I have a theory…

1January 19, 2018 by IPAlchemist

The patent litigation on pregabalin has been one of the most important UK patent stories of this century. It has raised important questions about the scope and meaning of second medical use patents, and has led to entirely new forms of court order (the Patents Court ordering NHS England to issue instructions on the prescribing of pregabalin by brand rather than generically). At the time, I wrote about the story extensively on the IPKat blog. (My last post is here; my posts on the main first instance decisions are here and here; links to earlier decisions are here.) I have been looking at the situation again because I am collaborating with Ben Goldacre and Richard Croker at the Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford on a study of the effect of the litigation on pregabalin prescribing and cost.

There was one recurring fact in the litigation that was often referred to but never explained. The Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC/GB04/034) based on the original product patent for pregabalin (EP0641330) was applied for in October 2004, following the granting of the European marketing authorisation to Pfizer for their Lyrica brand pregabalin, and granted in February 2005. But then in May 2013 the renewal fees required to bring it into force upon expiry of EP0641330 were not paid, so that it lapsed. It is a vanishingly rare occurrence to allow an SPC to lapse in this manner, and it must have been intentional. The question is, why would Pfizer do this? Incidentally, the owner of the patent and SPC is not Pfizer, but Northwestern University. There is no licence recorded on the UK IPO register, but licences are often not recorded and I presume that Pfizer (or one of its subsidiaries) is actually a licensee under the patent.

While looking into the case, I noticed that the US application from which EP0641330 claims priority is a continuation-in-part of an earlier US application. This is often a signpost to a possible self-collision issue, and so I took a closer look.

EP0641330 is based on international patent application WO93/23383, and claims priority from US application number 07/886,080. (“Claiming priority” is a system where you can file an application up to a year later than the earlier application, but it is regarded for the purposes of considering patentability [novelty and inventive step] as having been filed at the earlier date. Such a priority claim is valid only if the subject matter of the claim in question is present in both applications, and also provided that the earlier of the two applications is the first application for that subject matter). However, 07/886,080 is a continuation-in-part of US application 07/618,692, and a PCT application WO92/09560 was also filed claiming priority from that earlier US application.

The timeline is as follows:

27 November 1990 US 07/618,692 filed

20 November 1991 WO92/09560 filed

20 May 1992 US 07/886,080 filed

11 June 1992 WO92/09560 published

18 May 1993 WO93/23383 filed

Now, if we consider the right to priority of the claim to pregabalin in EP0641330, the corresponding subject matter is present in 07/886,080 and therefore on the face of it the first part of the test for a valid priority claim is satisfied – the subject matter is present in both applications. On that basis, WO92/09560 is not available as prior art, because it was published after 20 May 1992. (If this were not the case, I would expect the EPO examiner to have noticed it).

The difference between WO92/09560 and EP0641330 is that in EP0641330 pregabalin is claimed as a single enantiomer – the S-(+) enantiomer. In WO92/09560, by contrast, while the pregabalin molecule is disclosed, it is only made and tested as the racemate. However, WO92/09560 also states:

“The compounds made in accordance with the present invention can contain one or several asymmetric carbon atoms. The invention includes the individual diastereomers or enantiomers, and the mixtures thereof. The individual diastereomers or enantiomers may be prepared or isolated by methods already well known in the art.”

There is a plausible argument that this passage, in combination with the disclosure of the racemic pregabalin, is sufficient to count as a disclosure of the S-(+) enantiomer. In that case, however, WO92/09560 (or its priority application 07/618,692) is the “first” application for that subject matter, and not 07/886,080. That would make the priority claim invalid so that the effective date for considering the patentability of EP0641330 would become the filing date of WO93/23383, namely 18 May 1993. Thus WO92/09560 would become novelty-destroying prior art, because it was published before the filing date of WO93/23383 and thus EP0641330.

Now, all of this is arguable both ways, and it is possible that a court would not accept the argument. It is also a fairly subtle point, and I can imagine an EPO examiner missing it. It does not surprise me that the patent was nevertheless granted – on the face of it if the priority claim of WO93/23383 is valid, then WO92/09560 is not prior art at all since it was never filed at the European Patent Office as a European application. (If WO92/09560 has been filed as a European application, it would have been considered by the EPO examiner as “novelty-only” prior art under Article 54(3) EPC as being filed before, but published after, the priority date of WO93/23383). It is only if the additional criterion, whether 07/886,080 is the “first application” in respect of the subject matter of the S-(+) enantiomer of pregabalin, is considered that a potential problem becomes apparent.

None of this would apply in the USA, where the rules about your own earlier applications counting as prior art against your own application are completely different from the rules in Europe.

Also, a possible reason why the patent might be invalid is not of itself a reason for Pfizer to drop the SPC. Pharmaceutical patents are often found to be invalid by national courts, and although obviously the proprietor then loses the patent case, there is usually no further adverse outcome.

However, in 2009 the EU Commission published the Final Report in its competition inquiry into the pharmaceutical sector, which raised a number of questions about behaviours that had previously been considered unproblematic. Then in July 2010 the General Court upheld a finding of abuse of dominant position against AstraZeneca in relation to Losec (omeprazole), for actions including providing incorrect information about the date of the first marketing authorisation when applying for supplementary protection certificates, and this was upheld by the Court of Justice of the European Union in December 2012.

Moreover, in January 2012, the Italian Competition Authority sanctioned Pfizer for abuse of a dominant position relating to latanoprost consisting of various aspects including basing an SPC on a divisional application. This was quashed by the Regional Administrative Court of Lazio in September 2012, but then reinstated in February 2014 by the Consiglio di Stato.

All of these events together created a perception around 2010-2012 that, at least in respect of an SPC (if not necessarily in respect of a patent), the proprietor might (under competition law if not under any intellectual property law) be under a kind of good faith obligation that was more extensive than had previously been the case in Europe, and that the EU competition authorities might regard breach of such a good faith requirement as constituting an abuse of a dominant position. That perception is perhaps less prominent now, but at the time such views were widely discussed. A person might therefore have had a concern that a patent proprietor applying for an SPC based on a patent that the proprietor knew or should have known to be invalid, because the reason for invalidity was their own prior art, might be found to be an abuse of a dominant position under competition law.

There is no clear authority that it is an abuse of a dominant position to apply for an SPC based on an invalid patent (even where the patentee should know it is invalid, for example because the prior art is their own related application), but it may well have seemed in 2013 that this was the direction in which competition law was heading. The EU Commission can fine an undertaking up to 10% of worldwide turnover, so the risks involved if competition law comes into play are very high.

By not bringing the SPC into force, it was pretty much guaranteed that there would never be any litigation under the patent, since it would expire before the end of the data exclusivity period. On the other hand, if the SPC were brought into force, there would inevitably be litigation with generic companies, and there would be a risk that the patent might be found invalid for this self-collision reason. Once that reason became public by reason of the litigation, there could then arise a concern that this would lead to EU Commission action under competition law.

I do not know why Pfizer decided not to bring the SPC into force. However, this priority issue leading to a potential self-collision provides a plausible reason (and I have not seen any other possible reason suggested) why someone might have decided that it was too risky to bring the SPC into force. I wonder whether anyone can tell me whether it is anywhere close to the real reason.

Category Chemistry, IP (Intellectual Property), Patents, Science | Tags: patents, pregabalin, supplementary protection certificate

Report of the case management hearing on 19 July 2016 of the legal challenges to Brexit

0July 25, 2016 by IPAlchemist

The IP Alchemist and a couple of his colleagues from EIP went to Royal Courts of Justice on 19 July to watch the hearing to give directions and timetable to the various legal challenges to how, following the 23 June Referendum, the Government may take a decision to leave the EU and notify this decision to the EU under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union.

The hearing was before Sir Brain Leveson, President of the Queen’s Bench Division, and Mr Justice Cranston, from 10am to around 11.30am. Listed for Court 3, it was moved at the last minute to Court 4 because of pressure of numbers attending (both for the parties and in the public benches).

Claimants:

There were four main cases in existence or contemplation: Dos Santos (generally referred to by the name of the claimant), and Mishcon de Reya, Bindmans, and Croft (generally referred to by the names of the respective instructing solicitors). The Dos Santos case was the only one where a claim form had actually been issued and they wished to be the lead case (or at least joint lead case), but there was an issue of them not complying with the pre-action protocols (being the only reason why their case was ostensibly further advanced), and they were also seeking a protective costs order, which the Mishcon claimants were not. Dos Santos mentioned they would potentially withdraw their request for a protective costs order in order to remove this stumbling block to their desire to be the lead case. Despite this, it was decided that the Mishcon de Reya case, represented by Lord Pannick QC, would be the lead case. It was agreed by the Court that correspondence should have the litigants’ names redacted in order to avoid a continuation of the abusive and threatening communications that Mishcon and their clients have experienced as a result of this case (which had been notified to the Court by a letter from Lord Pannick QC). Sir Brian Leveson indicated that the Court took these incidents very seriously, and would be giving consideration to whether they may amount to contempt of court.

All of the other cases were to be stayed, but permission would be granted for them to intervene in the main case. Dominic Chambers QC for Dos Santos appeared to indicate that, if not the lead claimant, his client would prefer not to intervene but to be heard as an interested party.

The Bindmans case was organised and crowdfunded by Jolyon Maugham QC of Devereux Chambers – he was present at the hearing but not acting for any party (he tweeted for part of the hearing but had to leave to give a lecture). Information about the case can be read on his blog here:

https://waitingfortax.com/2016/07/08/article-50-our-letter-to-the-government/

The Croft case is apparently on behalf of some UK citizens resident in France, presumably challenging the possible loss to them of EU residence entitlement.

In addition there were two litigants in person, not present at the hearing, Hardy and Jacobson. At least one of these may be wishing to challenge the constitutionality of the referendum, in addition to the constitutional requirements for decision to leave the EU under Article 50.

In view of the large number of claimants and potential claimants, it was agreed to use group email as the method of correspondence. Concern was expressed that email correspondence could lead to leaks and therefore potential further abuse. Sir Brian Leveson made clear that he expected confidentiality to be observed and would take a dim view of any of the material surfacing on any blogs.

The defendant, originally assumed at least by the Dos Santos team to be the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, should in fact be the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union (“Minister for Brexit”). The defendant was represented by Jason Coppel QC.

Jason Coppel QC for the Government confirmed that the Government does not intend to make a notification under Article 50 before the end of the year. Accordingly, the hearing was set for mid-October. While not (as far as we understood) making a formal order, Sir Brian Leveson made clear that the Court expected to be informed if the Government changes its plans on timing. It appears to be assumed that there will be a leapfrog appeal, as Sir Brian Leveson believes this case meets the criteria to go straight to the Supreme Court, and no party challenged this. Sir Brian Leveson stated that the Supreme Court would be contacted immediately in order to ensure that there was space in the diary. The case will be heard by the Lord Chief Justice, but the other two judges are yet to be confirmed.

Timetable:

July 25th – deadline for Government to respond to the pre-action letters (so far the Government had not responded to any of the claimants, and Mr Coppel was unable to indicate whether any progress had been made on the responses yet)

July 29th- Mishcon de Reya claim to be issued

September 2nd- detailed response required from defendant

September 14th- skeleton arguments from claimant must be submitted

September 21st- deadline for submissions from interveners and interested parties (only if additional to points made by claimant)

September 30th- skeleton arguments from defendant must be submitted

October 17th- trial to be held for 2-3 days

If the hearing needs to be moved, for example if Article 50 to be activated earlier (or later) than currently planned, then other dates can be moved accordingly.

Sir Brian Leveson indicated [paraphrasing somewhat but more or less in his words]: You should have no doubt that the Court takes this case extremely seriously and will act expeditiously for its disposal; the Lord Chief Justice will require concision and expedition; and, concerning the timetable, there will be liberty to apply for variation but “not by much”, and case will “continue to be managed over the summer”.

Good sources of information about these cases are the Jack of Kent blog (see for example here) and its author David Green’s Twitter @DavidAllenGreen; and also on Twitter Joshua Rosenberg @JoshuaRozenberg. Other reports of this hearing are in The Guardian here and Full Fact here.

Category IP (Intellectual Property), Political | Tags:

The vigil for Orlando – thoughts from a gay man in London

3June 15, 2016 by IPAlchemist

I am certainly not the first person to write a piece like this and I am sure I won’t be the last. But the events of the last few days, and especially the feelings that arose in me when attending the Vigil in Soho after the Orlando shootings, have made me want to record something about how I see what it is like to be gay. Here, now, in London, in 2016.

I write “gay” because I identify as a gay man. I also identify as part of the LGBTQI+ community, but this is specifically about my story, and I will come to the issues within our community in a moment.

Being gay puts you into a minority. We gays spring up around the country, and for many of us, like me, we don’t know any others for a long time. I heard words like “poof” in the schoolrooms tossed about like punches as clearly a bad thing, but it was a while before I had any sense of what it actually meant, and then a while more before that slow horrible realisation dawned that it possibly meant me. And, of all the people I knew, only me – no-one else seemed the same.

For quite a few years I thought my otherness was something that might change, encouraged by well-meaning interventions from people (sorry, Mother) assuring me that being interested in girls was something that was normal to develop quite late. But by the time I was 19 I realised and accepted that gay was what I was. For several years before that I had the bizarre delusion that if I “did anything about it” my sexuality would become fixed as gay, but that if I didn’t perhaps I would slowly begin to fancy the opposite sex, as I had been taught. So I finally came out at 19, had my first “adult” consensual sexual experience (still illegal at the time, mark you, as the decriminalisation only applied to those over 21), and thought that was all there was to it. I had “come out”. It was done, there was no further step to be taken. But it turns out, it’s a little bit more complicated than that.

Gay men like me are a minority virtually all the time. Most of us spend most of our time overwhelmingly surrounded by people who are not as we are. I had heard of mythical places in America where there were not only gay bars but gay establishments of all kinds so that it was possible to live in an enclave where your sexuality was normalised. That was a long way from my reality in Yorkshire, Oxford, or even London.

So what is the effect on us of being a perpetual minority? We dissemble, we protect ourselves, we are perpetually vigilant for how “safe” it is to let slip something of our true identity. We censor ourselves constantly. And we seek out, for perhaps just a few hours a week or a month, those places where we know we are safe being completely unguarded.

Although that itself carries dangers that there was no-one there to warn me about. The gay scene holds out an image of the “gay lifestyle” where everyone is impossibly attractive, glamorous, stylish, promiscuous, wealthy – works hard, parties hard, and has it all. And drinks a lot. Of course. How else are the feelings of not belonging, shame, fear of discovery, and inadequacy to be silenced? I thought I wanted the mirage of the gay lifestyle, and I thought I could have it. It was not until many years later that I discovered that the image I had been peddled was an illusion, and a destructive one at that.

But the gay scene for all its destructive qualities remains our lifeline and I still seek it out. For even now, after all the legal protections and freedoms that we have won in the UK, it is the only place where I am normal.

Some of us, paradoxically, seek solace and comfort in institutions that actually work against our self-acceptance. For example many of us embrace a religion that, however “compassionately” it may be put, tells us that our sexuality is deviant and unacceptable. Some of us consider priesthood. A few actually get ordained. But sadly I am coming to the conclusion that it is not possible to be a fully authentic self-loving gay man in most of the mainstream Christian denominations.

Another thing we do and that I regret is to define ourselves, as I see it, to the level of “minimum unacceptability”. This seems to me to be based on the idea that if we present to the potentially hostile environment around us the minimum set of things about ourselves that might be problematic, we might be safer. So “I am gay but I am straight acting.” “I can’t bear camp people”. We distance ourselves to the point of demonisation from those whose dress, behaviour, sexual practices etc might be regarded as less “acceptable” than our own. Please pick on that person, not on me. I used to. A lot. I try not to any more. I came to realise that we stand together, or not at all.

A sad result of that is that our LGBTQI+ “community” sometimes isn’t actually much of a community as we struggle to define ourselves as less unacceptable than others. Gay men are quite prone to misogyny. We can be racist too. And we are inherently no more tolerant or respectful of transgender people than anyone else. So our “community” often feels to me like a disparate group of marginalised people, huddling together uneasily for mutual protection. Because there is safety in numbers, right? I now feel rather ashamed of the privilege I have enjoyed of being basically able to choose how much of my “otherness” I want to display at any time, while over the last decade or so coming to realise that others in my tribe are not able to hide as effectively as I could and so don’t have that choice.

But although we are not at all immune to bigotry and intolerance, I would observe that most LGBTQI+ people have, because of the minority in which we find ourselves, circles of friends and companions of much greater diversity than if we had not belonged to our minority. Within our minority other boundaries are more easily transcended. We are people that otherwise would not mix.

Fear, self-protection, safety in numbers. That permeates our whole existence. Even here in London my friends tell me that in many parts of our city they don’t feel safe holding hands with their partners, despite the legal protections that we apparently enjoy. We scan, we assess, and then we decide whether it is safe to act naturally or to hide.

And so we come to the Orlando massacre. We feel shock, and sympathy for the many victims, even though they may be in another continent from us. We feel a sense of solidarity. We understand that, yet again, our community has been attacked by someone who hates us for whatever reason. Many of us who live in countries with some social acceptance and legal protections feel again just how fragile those protections are, how little they may actually protect us, and how easily they could be taken away again.

And then we observed a narrative in the media – this is not about gay people. Starting with the incident on Sky news where Owen Jones was talked down for correctly asserting that this should be seen as a homophobic hate crime, and continuing with comments on social media, people, including those we counted as our friends, were trying to erase from the narrative that it was an atrocity against LGBTQI+ people, insisting it was about “ALL PEOPLE” and that the “wider context” that it fits into is one of islamic terrorism, or perhaps US gun control. For us, the “wider context” that it fits into is the one of the long history of persecution of gay people. We began to feel that if we did not make this event part of our history, other people were going to hijack it to make it part of theirs.

Initially I thought it was only me that felt this way, but my friends who also went to Soho on Monday reported similar responses, and Douglas Robertson wrote a piece in the Independent that similarly resonated. Many of us were angry.

That is why I went to Soho on Monday, and that is why, two days later, I still feel very emotional and reconnected with some of the activism that I had when I was younger, that had recently begun to fade.

So our safe places are important. The gay scene is under threat from rising property costs, redevelopment, and technology-driven social change whereby people can arrange to meet each other online rather than having to go to a real-world venue. But we need those places and this week many of us are remembering that again. Our protections are fragile, and easily lost. Our fight is far from over.

Category Political | Tags:

An Alchemist in Paris – the Café Des Chats Bastille

0May 10, 2015 by IPAlchemist

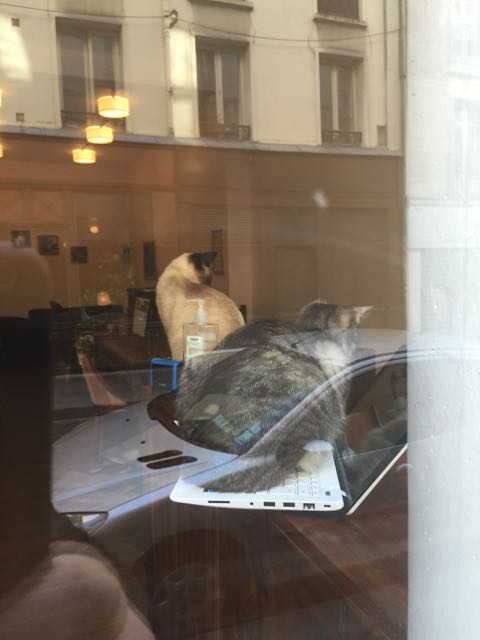

Just round the corner from my hotel was a cat cafe. Yes, really. The place is crammed with custom feline furniture and moggy perches but look where this one has plonked himself. Sorry for poor picture quality due to reflections in the window but I think you get the idea. #leprocrastichat #nottakingreservationsatthemoment

So having sneaked a photo at the cat cafe I had to come in. There are loads of cats – apparently 12 in total but three lined up by me. It is adorable.

The only problem – how to stop the blighters from eating my food (as firmly instructed) while observing the equally firm instruction to “not make the cats do anything they don’t want to”. An unsolvable conundrum.

Category Travel | Tags: Cat Cafe, Paris

An Alchemist in Paris – Dining III

0May 10, 2015 by IPAlchemist

Turns out I was too hasty in condemning the queue at Angelina. This time however, and exhausted from the Louvre and the Mont Blanc debacle, the queue is scheduled. The third suggestion from Andrew was Chartier, but he warned me of likelihood of wait since they don’t take reservations. It closes at 10 so I thought I better go straight there, even though it is only an hour since the end of Mont Blanc #2. Sure enough there were at least 30 people waiting. However, there was a table waiting for a solitary friendless soul so I jumped past all the couples, threes, and fours.

I plumped for endive salad with Roquefort, choucroute alsacienne, and some pommes frites coz they looked nice. Steered clear of tete de veau and andouillette for reasons which regular readers will understand. Order is now duly written on my tablecloth. The room is cavernous and the sound of conversation echoing. I hope they take a long time to bring my food. I am sure they won’t.

So, judging from what appears only, since I have never made it myself, choucroute alsacienne is finely shredded pickled cabbage boiled with ham and assorted charcuterie and served together with the odd boiled potato lurking therein. If you want to try it in London I highly recommend the Delauney. At Chartier it was also lovely although – as with the whole restaurant- rather more basic. I attach the now mandatory pic above. It was also quite the best value meal I have had so far. My starter of endive salad had so much Roquefort on it I can’t imagine how they can buy it, let alone sell it, for the few euros that it cost. The frites were probably ill-advised but delicious so I was replete after only the two courses.

Category Travel | Tags: Chartier, dining, Paris